European Explorer’s Search for the Northwest Passage

Although Peterson’s Point Lake Lodge is well-known as one of the finest sport fishing locations in the NWT, there’s far more than fish here.

Ancient, deeply incised trails attest to heavy use of the area by caribou for many hundreds of years, and also to indigenous hunters pursuing the caribou. Dene, Chipewyan and Inuit all hunted in the area, depending on caribou, musk oxen, and moose, plus waterfowl, and later, furbearers.

European explorers began entering the North American arctic with explorations into Hudson Bay beginning in 1610 (Henry Hudson) and by the late 1600s, trading companies were establishing posts on the bay. The coming of traders and whalers changed the life of the Indigenous people from subsistence to trade-based lifestyles. They brought strange new items like the steel needle, the rifle, metal tools, fabrics, and many other items, making life easier, but more complicated. People began travelling from the west to trading posts on Hudson Bay to obtain this new technology.

Samuel Hearne was among the first explorers to travel into the unknown lands northwest of Hudson Bay. Guided by Matonabee, a Chipewyan/Cree leader, and a group of his followers, Hearne was seeking information about new trading connections and about the fabled “copper mines” (and rumours of gold). In 1761, Hearne passed just to the east of Point Lake on his way to the Coppermine and was the first European to see the Arctic Ocean.

The desire to seek a shorter route to the riches of the Orient sparked Britain’s desire to locate a “Northwest Passage”, a sea route across the top of North America. John Franklin of the Royal Navy made three attempts to define this route. His first attempt, in 1819-1821, an overland expedition, began on Hudson Bay. His small British team of only 5 men was augmented by additional teams of French Canadian voyageurs, four interpreters, and in 1820, a large number of Dene members of a band led by Akaitcho, from northwest of Great Slave Lake. Franklin’s party headed north, up the Yellowknife River and Snare River. Once they reached “Winter Lake”, all worked to build wintering cabins, which they named Fort Enterprise.

In June of 1821, they headed north, travelling on foot, “man-hauling” heavy sleds, including three birchbark canoes, one of which had to be abandoned on the shore of Point Lake. It was an awful slog; they often travelled in 2 ft. of overflow on the lake ice, passing near the present site of Point Lake Lodge. The Dene men hunted for food for a large group as nearly 100 people from Akaitcho’s band (including women, children, and dogs) who were travelling with them. In mid-June, most Dene went west to their traditional summer camps near Napaktulik (Takijuq) Lake, to fish and hunt musk oxen. Some remained with Franklin’s group. Spring was coming on; the birds were returning – they even found an Eskimo curlew nest at the east end of Point Lake. Unfamiliar with the country along the coast, most of the Dene left soon after they were on the Coppermine River.

Franklin’s group of 20 men continued down the Coppermine and across the arctic coast in two birchbark canoes, mapping, looking for good harbours, minerals, and much more. Richardson was collecting new species of birds, mammals and plants. The “Orders” for the expedition were complex and demanding.

As winter approached, the expedition turned back at the Kent Peninsula, when it became evident that they would not make it to Hudson Bay that year. To preserve the information collected, and get it back to England, they had to survive. They crossed the barrenlands on foot, under desperate winter conditions, losing half the members of their party including Midshipman Robert Hood, killed by one of the voyageurs when things became desperate. It’s a macabre, chilling story.

The journals of several members of the expedition survived, and the maps and information added greatly to the growing knowledge of the geography of North America.

After returning to England, the journals and maps were published by 1824, and the Admiralty then supported a second overland expedition, from 1825-1827. On this one, Franklin’s team descended the Mackenzie River to Great Bear Lake, overwintered, and then the expedition split, with Franklin’s group heading west from the mouth of the Mackenzie to what is now Prudhoe Bay, Alaska. Richardson’s team headed east from the Mackenzie delta to the mouth of the Coppermine, then inland across Great Bear Lake. Both teams mapped the routes, and returned to winter at Fort Franklin (now called Deline). They travelled in wooden boats, and this expedition was better supported, no lives were lost, and the coastline mapped exceeded 1200 miles. The information gained certainly helped delineate the Northwest Passage.

In 1845, Franklin’s third expedition entered the Arctic from Lancaster Sound. It was a marine expedition, in two ships, the Erebus and Terror, comprised of 122 men. After wintering at Beechey Island on the north side of Lancaster Sound, the expedition vanished. Details of the fate of Franklin and his men are still being worked out, but both ships have been found, along the coast of King William Island and in the Simpson Strait. They lacked only about 150 miles of “closing the Passage”. It is a truly intriguing chapter of Canadian history.

All this makes for a fascinating story, which we explore in detail at the Lodge as part of the Barrenland Naturalist Tour. Depending on weather, it may be possible to visit a Franklin campsite location on Point Lake. Of course, little is left after 200 years, but for history buffs, it is fascinating to actually be there, and to realize the difficulties facing these explorers during a time when the climate was much colder than today.

Written by: Page Burt

Suggested readings:

When seeking readable versions of the explorer’s journals one editor’s work excels: C. Stuart Houston. He was a physician, expert radiologist, and an amazing historian, ornithologist, and writer. His annotations and appendices add much to the relevancy of the journals.

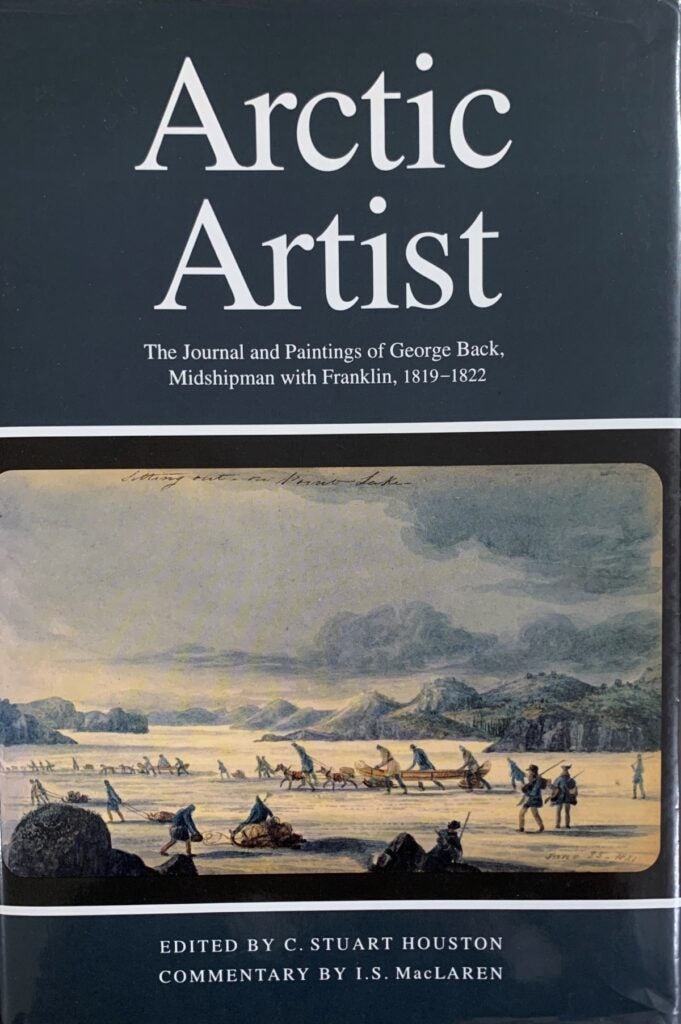

C. Stuart Houston. 1994. Arctic Artist, The Journal and Paintings of George Back, Midshipman with Franklin, 1819-1822. McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Houston, C. Stuart. 1984. Arctic Ordeal, The Journal of John Richardson, Surgeon-Naturalist with Franklin, 1820-1822. McGill-Queen’s University Press.

C. Stuart. Houston. 1974. To the Arctic by Canoe, 1819-1821. The Journal and Paintings of Robert Hood, Midshipman with Franklin. Arctic Institute of North America, McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Other Books: Davis, R.C. (Editor). 1995. Sir John Franklin’s Journals and Correspondence: The First Arctic Land Expedition, 1819-1822. Champlain Society, and Royal Canadian Geographic Society.

The book’s cover image depicts the expedition journeying across Point Lake.